The Power to Recall MPs: A Right on Pause?

The Power to Recall MPs: A Right on Pause?

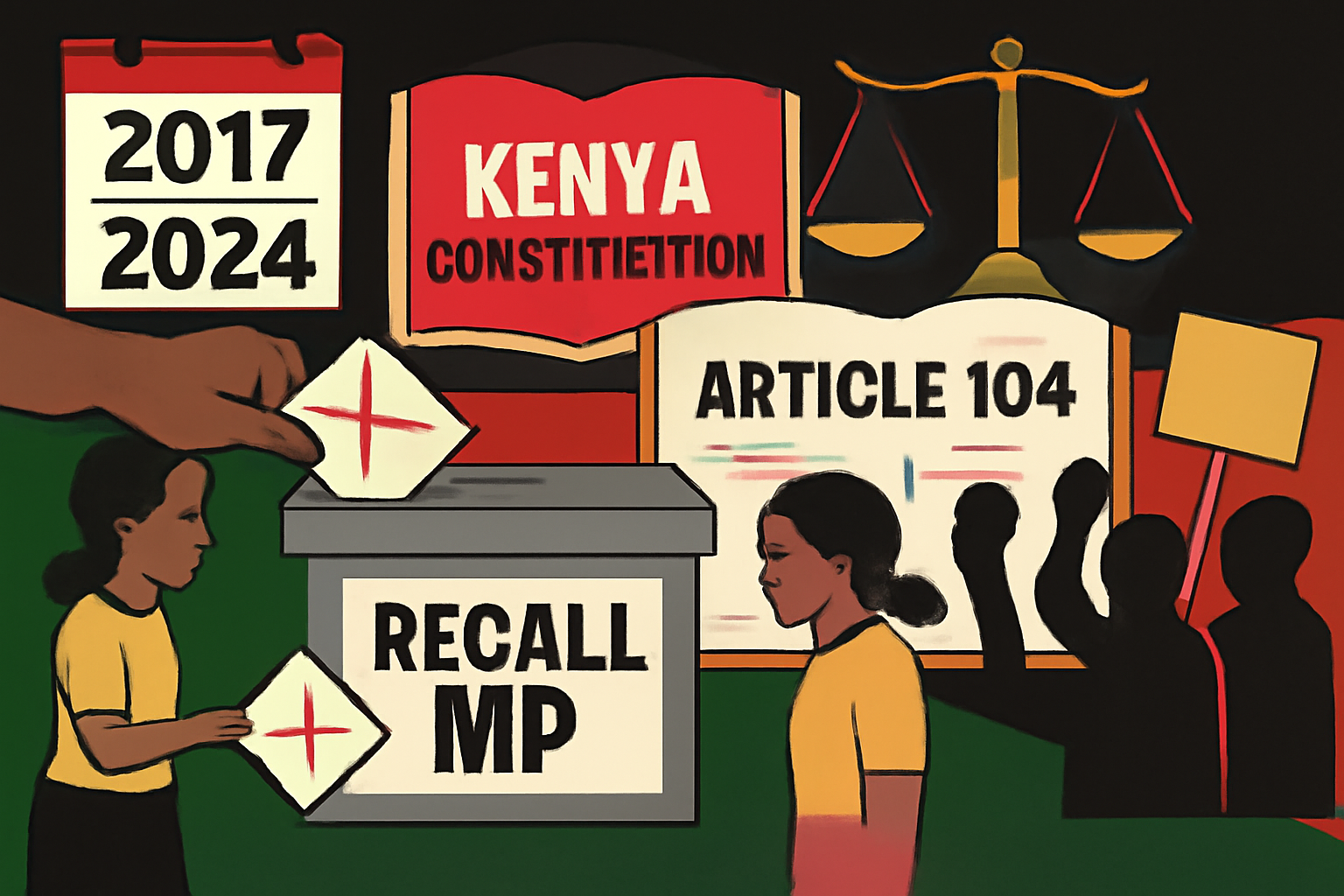

In the recent political landscape of Kenya, the issue of recalling Members of Parliament (MPs) has stirred widespread discussion. Citizens across the country have expressed concern over accountability, pointing to the constitutional right that allows the electorate to remove elected representatives before the end of their term. This right, embedded in Article 104 of the Constitution, was designed to ensure that public servants remain answerable to those who put them in office. But as it turns out, that right is currently unenforceable, and here’s why.

The Recall Right: Constitutional but Dormant

The Kenyan Constitution clearly states in Article 104 that voters have the right to recall MPs. To operationalize this constitutional promise, Parliament passed the Elections Act in 2011. Under Part IV, the Act detailed the procedure through which citizens could initiate a recall.

However, in 2017, the High Court ruling in Katiba Institute & Another v Attorney General declared variables like the grounds for recall and need for a court order to warrant the recall unconstitutional. The court found parts of the recall law to be discriminatory, particularly the different thresholds applied to MPs and county legislators. As a result, Sections 45(2), (3) and (6), 46(1)(b)(ii) and (c) and 48 of the Elections Act and sections 27(2)(3) and (6) and 28(1)(b)(ii) and (c) of the County Governments Act were deemed as invalid. Unfortunately, no replacement framework was put in place for MPs, although the law for recalling Members of County Assemblies was adjusted. Since that judgment, Kenyans have had the constitutional right in theory, but no legal avenue to exercise it in practice.

Elections (Amendment) Bill, Senate Bill No. 29 of 2024: What’s changing?

To address the unconstitutional recall framework, Parliament introduced the Elections (Amendment) Bill, Senate Bill No. 29 of 2024, on July 7, 2024. This Bill proposed a bold overhaul by repealing Sections 45, 46(1)(b)(ii) & (c), and 48 of the original Elections Act. Initially, the Bill sought to remove legal justifications for recall entirely. It eliminated the need for a High Court order and proposed that recalls be initiated through petitions filed directly with the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), as outlined in Clause 26 of the Bill. However, the original draft faced criticism for failing to set clear grounds for recall, potentially diluting the seriousness of the mechanism.

In response to public feedback and legal recommendations, the Senate amended the Bill on February 12, 2025. These amendments reintroduced a structured approach, with clearly defined recall grounds. Subsection (2) was substituted to include updated criteria, while subsections (3) and (6)—which previously required a court order and barred election losers from initiating recalls—were removed. This was a significant shift aimed at empowering citizens rather than limiting them.

Section 46 was also revised to delete outdated voter eligibility limitations, and Section 48—which had required a 50% voter turnout threshold to validate a recall election—was repealed. The removal of this threshold is widely seen as a democratizing move that makes the recall process more attainable for ordinary citizens. Despite the foregoing, the legislation lacks effect following its impending enactment which legally breathes life to article 104.

Importantly, constitutional lawyer Evance Ndong argues that IEBC’s claim of being unable to act without enabling legislation is legally flawed. He asserts that Article 104 of the Constitution is self-executing—meaning it does not require additional legislation to be enforceable. According to Ndong, IEBC’s stance reflects outdated legal formalism that wrongly places statutory law above constitutional authority. He likens this to colonial-era thinking, where rights were only valid if Parliament endorsed them. Evance emphasizes that Kenya’s post-2010 Constitution is transformative, designed to empower citizens directly. He draws parallels to Article 10 on public participation, which is judicially enforceable even without specific statutes. In his view, IEBC should interpret Article 104 in a purposive, value-driven manner and facilitate recalls as a constitutional obligation—not wait for Parliament’s permission.

To buttress this claim, Ndong references the case of Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others (CCT 12/05), where the South African Constitutional Court held that public participation is a constitutional requirement in law-making processes. The Court emphasized that constitutional obligations—such as those found in participatory democracy clauses—are not merely aspirational but judicially enforceable, even in the absence of enabling legislation.

He also cites Centre for Rights Education and Awareness (CREAW) v Attorney General [2013], which is a more local precedent, where the Court upheld the principle that constitutional rights are enforceable even in the absence of precise statutory frameworks. Ideally, the interpretation that ensures access to justice takes prevalence. This precedent aligns with Evance’s view that recalling MPs should be administratively facilitated by IEBC in recognition of the Constitution’s transformative intent.

What Does This Mean for the Voter?

Mr. Evance Ndong’s article draws on a rich constitutional and jurisprudential foundation to argue that Article 104 is self-executing and does not require enabling legislation to be enforceable. He correctly critiques IEBC’s reluctance as rooted in outdated legal formalism and emphasizes the transformative nature of Kenya’s 2010 Constitution—one that places citizen agency at the centre of democratic accountability.

However, his argument focuses almost exclusively on procedural access to the recall mechanism: the right to petition, the route through IEBC, and the removal of High Court prerequisites. What remains absent is a discussion of the substantive legal grounds required to trigger a recall. These grounds are not optional technicalities. They are the legal anchors without which any procedural step becomes constitutionally hollow. The Constitution does not empower voters to recall an MP simply at whim; there must be cause. Without clearly articulated and legislated grounds, even a “self-executing” right runs the risk of being vague and legally indefensible.

That’s where the distinction between a transformative Constitution and institutional boundaries comes into play. While the Constitution empowers citizens directly, non-legislative institutions like IEBC or the Judiciary cannot legislate by proxy. They can critique, recommend, interpret, and even strike down unconstitutional laws—as the courts did in the Katiba Institute case—but they cannot bypass Parliament’s mandate to define legal thresholds and safeguards through legislation.

This brings us to the issue at the heart of the delay: political goodwill. Parliament’s slow action on recall legislation for MPs stands in contrast to its swift amendment of the County Governments Act to fix discriminatory recall provisions for MCAs—also struck down in the Katiba Institute ruling. The precedent exists, the court guidance is clear, and the Constitution demands it. Now, what’s needed is urgency. The longer Parliament withholds action, the more the constitutional promise of mid-term accountability remains out of reach.

The enactment of a coherent, accessible recall framework under the Elections Act is not just a procedural fix—it’s a democratic necessity. The window to restore public trust and fortify participatory governance is open. Parliament simply needs to step through it.

Final Thoughts

The right to recall MPs in Kenya has long existed on paper but remained frozen in practice due to discriminatory laws and procedural obstacles. With the incoming passage of the Elections (Amendment) Bill, Kenya is turning a corner. The latent changes uphold the High Court’s 2017 ruling and introduce a more equitable, citizen-centric recall mechanism.

Electoral Law and Governance Institute for Africa (ELGIA),

is a Continental Organisation working to strengthen

and consolidate constitutional democracy,good governance,

human rights,institutional strengthening of

parliament and electoral processes in Africa.

Copyright @ 2025 . ELGIA.